- The Dashboard

- Posts

- How to Be Wrong 9,900 Times Without Going Broke

How to Be Wrong 9,900 Times Without Going Broke

What Norwegian triathlon taught me about creative testing

Part 1: The Day Triathlon Got Solved

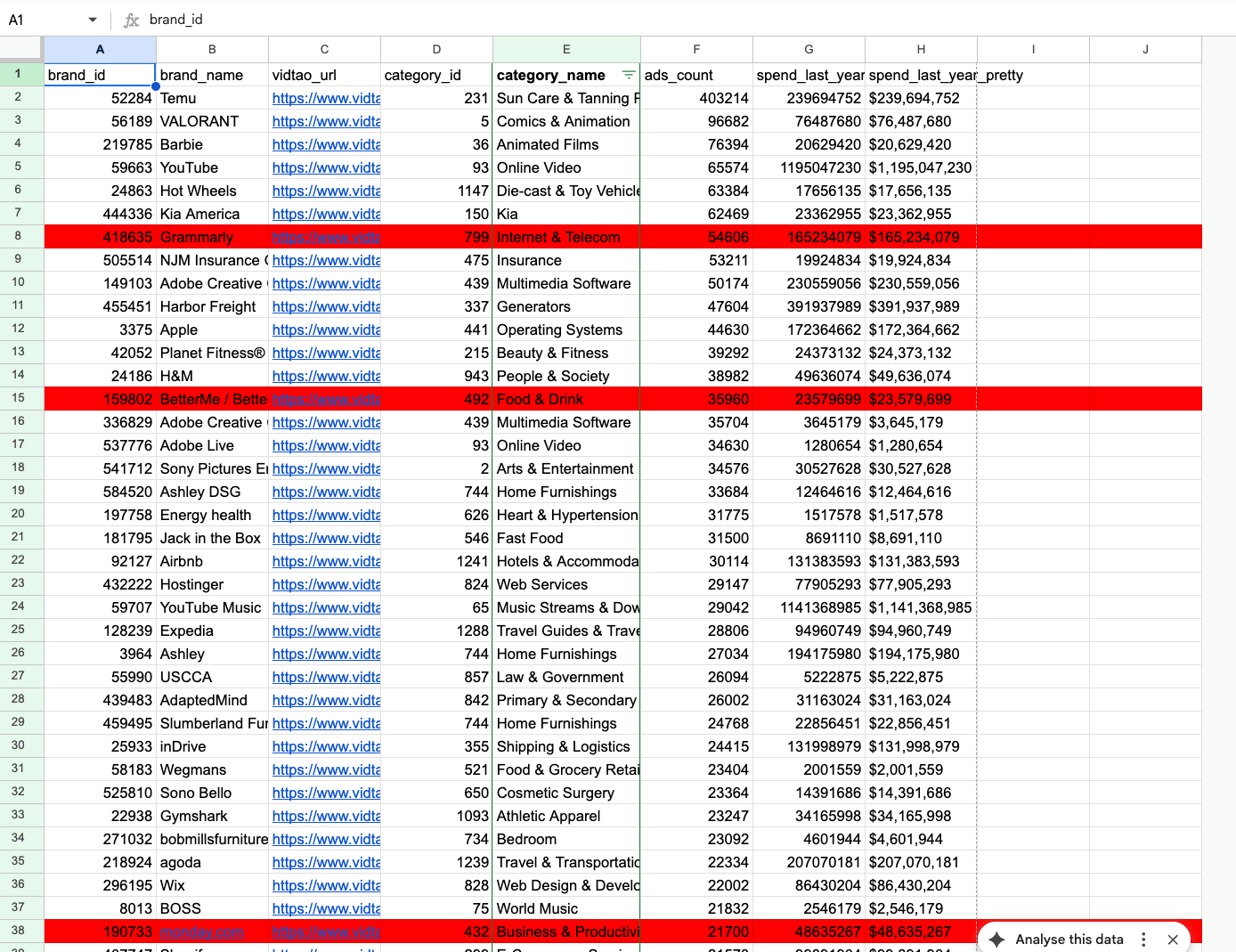

The top 10 direct response brands on YouTube have each tested somewhere between 5,000 and 10,000 ads.

The correlation between spend and ad volume is almost perfect. I love to describe them as companies that can afford to be wrong 9,900 times while finding the 100 that work.

How do you build that?

How do you create a system where you can test 10,000 hypotheses without blowing up?

I found the best answer in the last place I expected: Norwegian triathlon.

In 2021, a 27-year-old named Kristian Blummenfelt won Olympic gold. Three months later, he raced his first-ever full Ironman and broke the world record. Six months after that, he became the first human to finish one in under seven hours.

Olympic triathletes and Ironman athletes are different animals. You don't switch between them in three months while breaking world records.

But he did. And his training looked completely wrong.

35 hours a week. Sometimes 40. Pricking his finger mid-workout like a diabetic. Jogging so slowly that weekend warriors passed him.

His coach? An engineer who tracked lactate, oxygen, even fecal samples.

Everyone thought they were crazy.

What they actually built was a system for testing thousands of hypotheses per year—with capped downside on every single one.

That's what this article is about.

Fair warning: I'm going deep into mitochondria, lactate thresholds, and fat oxidation. You'll wonder why you're reading about triathlon in a newsletter about analytics.

Stay with me. By the end, you'll understand why the brands that win aren't the ones with the best ads—they're the ones that built organizations where learning compounds and mistakes don't kill you.

Part 2: The Engine Inside You

The Mitochondria Story

Imagine your muscles are cars. They need fuel to move.

Inside each muscle cell are thousands of tiny power plants called mitochondria. Their job: turn food into energy your muscles can use.

More power plants = more energy = you can go faster, longer.

Simple so far.

The Two Fuel Types

Your body transforms food into two main fuels:

Sugar (carbohydrates): Burns fast. Like paper in a fire. Great for sprints, but you only have enough stored for maybe 90 minutes of hard effort. When it runs out, you are done! Bye.

Fat: Burns slow. Like a mortgage. You have almost unlimited supply—even lean people have tens of thousands of calories stored as fat. But (there is always that freaking but) your body can only burn fat when there's enough oxygen, and only if you have enough mitochondria to do the burning.

The Byproduct That Tells You Everything

When you burn sugar for energy without enough oxygen—like when you're sprinting or working really hard—your body produces a byproduct called lactate.

Think of it like smoke from a cigarette. The more you inhale, the more there is to exhale.

Here's what most people get wrong: lactate isn't the enemy (unlike cigarettes—guys, don't smoke). It's byproduct recycled by your muscles as fuel. Your body is constantly producing lactate and clearing it away, even at rest (around 1.5 mmol/L in your blood just sitting there).

The problem comes when you produce lactate faster than you can clear it. That's where pain starts. That burning sensation in your legs during an all-out effort? That's lactate brother (and the hydrogen ions that come with it) building up faster than your body can process it.

Now comes the fun part (I swear I'm going to connect this with D2C and info products, just stay with me. Believe in me!):

The rate at which lactate accumulates tells you exactly what fuel system you're using.

Low lactate (under ~2 mmol/L): You're burning mostly fat, aerobically. Sustainable for hours.

Moderate lactate (~2-4 mmol/L): You're at the edge. Burning a mix. This is the threshold zone.

High lactate (above ~4 mmol/L): You're burning sugar fast, outpacing your oxygen supply. Clock is ticking. You are going to die soon. Not literally, more abstractly. Like it would feel better to die than continue whatever the hell you are doing.

Lactate isn't just evolution's way to add more misery to our existence. It's a real-time metric that tells you exactly how hard your engine is working, and which fuel is using.

Why Fat Is the Holy Grail

Fat is the superior fuel. Here's why:

Abundance: Even a lean (hate these people) athlete carries 30,000-50,000 calories stored as fat. That's enough to run multiple marathons back-to-back. Sugar? You store maybe 2,000 calories as glycogen. That's 90 minutes of hard effort, tops.

Efficiency: When you burn fat aerobically (with oxygen), the process is clean. Your body produces energy steadily, lactate stays low, stress hormones stay calm.

Recovery: Fat burning is gentle on your system. You can do it for hours and wake up the next day ready to go again. Sugar burning—especially without enough oxygen—creates metabolic stress. Lactate accumulates, hydrogen ions build up, your muscles acidify. That takes days to recover from. Loser.

The math is simple: If you can do the same pace while burning mostly fat instead of mostly sugar, you last longer, recover faster, and can train again sooner.

Elite endurance athletes aren't tougher. They're not suffering more (Fuck of Gary V). They've just shifted their fuel source.

At any given pace, they burn more fat and less sugar than you or I do.

Same speed. Different fuel. Completely different outcome.

How Do You Burn More Fat?

Here's the problem: your body prefers sugar when intensity rises.

Sugar is fast. When you need energy NOW—sprinting, climbing, surging—your body grabs the quick fuel.

Fat burning requires oxygen. It's a slower process. The moment oxygen delivery can't keep up with energy demand, your body switches to sugar.

So how do elite athletes burn fat at intensities where normal people are "eating" all their sugar?

Mitochondrial density.

Remember those power plants inside your muscle cells? The more you have, the more oxygen you can process, the more fat you can burn at higher intensities.

Think of it like lanes on a highway.

A two-lane highway gets congested fast. Traffic builds up. Everyone's stuck.

An eight-lane highway handles the same number of cars easily. Traffic flows.

More mitochondria = more lanes = more oxygen processed = more fat burned before your body needs to switch to sugar.

An untrained person might start burning mostly sugar at a slow jog. Their limited mitochondria can't process enough oxygen to meet the demand.

A trained athlete with high mitochondrial density? They're still burning mostly fat at paces that would have the untrained person feel existential misery of human existence.

Same intensity. Different fuel. Because different engine.

How Do You Build More Mitochondria?

Your body builds mitochondria when you force it to process oxygen over extended periods.

This happens at multiple training intensities—but with different tradeoffs:

Low intensity (lactate under ~2 mmol/L): Mitochondria are built here too. Slowly, steadily. The adaptation signal is weaker per hour, but you can do this for hours without accumulating fatigue. Volume is your friend (if you have any). Five hours of easy aerobic work sends a meaningful adaptation signal—and you can do it again tomorrow.

Threshold intensity (lactate ~2-4 mmol/L): Stronger adaptation signal per hour. You're pushing your aerobic system to its limit, demanding it grow. But this work is harder to recover from. You can't do five hours of threshold. Maybe 60-90 minutes in a day, broken into intervals, if you're elite.

Above threshold (lactate above ~4 mmol/L): Different adaptations—more anaerobic capacity, pain tolerance, VO2max. But the recovery cost is enormous. A truly maximal session might require 48-72 hours before you can train hard again.

The insight: Total adaptation = signal strength × time accumulated.

Low intensity: weak signal × many hours = meaningful adaptation

Threshold: strong signal × limited hours = meaningful adaptation

Above threshold: very strong signal × very few hours = diminishing returns for aerobic development

The traditional mistake was chasing the strongest signal (above threshold) while ignoring the math. Yes, brutal intervals send a powerful adaptation signal. But you can only do 45 minutes per week before you're overtrained.

The Norwegian Math

The Norwegians optimized the equation differently.

80-90% low intensity: Builds aerobic base through sheer volume. Hours and hours of easy work, accumulating mitochondrial adaptations slowly but consistently. AND—critically—this easy work allows recovery from the threshold sessions.

10-20% at threshold: Strong adaptation signal, carefully controlled. They don't go above threshold because the recovery cost isn't worth it. They'd rather do two threshold sessions today and two more tomorrow than one brutal session that wipes them out for three days.

Almost nothing above threshold: The math doesn't work. Too much recovery cost, not enough additional adaptation.

The result: more total adaptive stimulus per week than athletes who train "harder."

A traditional athlete might do:

2 brutal VO2max sessions (90 min total at high intensity)

"Easy" days that aren't actually easy because they're still recovering

Maybe 6-8 hours total volume

A Norwegian athlete does:

4-6 threshold sessions (controlled, not maximal)

Truly easy days that actually build base AND allow recovery

30-35 hours total volume

More hours. More adaptation. Less damage.

The Norwegian Flip

This is what Blummenfelt's coach Olav Aleksander Bu figured out.

Bu is an engineer by training. He looked at the data and asked a different question:

Not "how hard can we push?" but "how much threshold work can we accumulate without breaking?"

The answer: far more than anyone thought—if you protect recovery.

The method:

80-90% of training at low intensity. Genuinely easy. Lactate under 2 mmol/L. Builds base AND allows recovery from threshold work.

Double threshold days. Two sessions per day at threshold intensity—but controlled. Lactate held at 2.5-3.0 mmol/L, not higher. Maximum aerobic stress, minimum recovery cost.

Lactate monitoring as a circuit breaker. Mid-workout finger pricks to check blood lactate. If it drifts above their individual threshold (around 2.5-3.0 mmol/L for the Norwegian athletes—lower than the textbook 4 mmol/L), they slow down. Immediately. No ego.

Massive volume. Blummenfelt trains 30-35 hours per week. Because most of it is easy, and the hard work is precisely controlled, his body can absorb it.

The result: more total time at threshold per week than athletes training "harder." More adaptation signal. More mitochondria. Higher fat-burning capacity.

They don't train harder. They train more—at the exact intensity that builds what matters.

Part 3: Why This Actually Works

The Barbell Principle

Look at what the Norwegians actually built:

One side: Protected stability. 80-90% of training is genuinely easy. Lactate under 2 mmol/L. Recovery happens. Base builds.

Other side: Aggressive asymmetry. 10-20% of training is precisely hard. Threshold work, controlled by lactate monitoring. Maximum adaptation signal, minimum recovery cost.

The middle: Eliminated. No "medium hard" sessions. No "pretty tough" efforts. No grinding that feels productive but delivers neither recovery nor adaptation.

This is the barbell principle: load the extremes, avoid the middle.

Why does the middle kill you?

A "medium hard" effort is the worst of both worlds. Too hard to recover from properly. Too easy to trigger strong adaptation. You accumulate fatigue without accumulating fitness.

Most athletes live in the middle. They go "kinda hard" most days. Their easy days aren't easy. They're always tired, never really adapting.

Capped Downside, Compounding Upside

Here's why this structure creates exponential separation over time:

The safe side compounds quietly.

Every hour of low intensity work deposits into the mitochondrial bank. Small but it adds up, and keeps accumulating.

The risky side compounds aggressively—because the risk is capped.

Threshold work is where things normally go wrong. Push too hard, drift above threshold, and one session can cost you three days of recovery. Do that twice a week and you're, as we explained, dead. Not literally, more metaphorically.

For Norwegians the lactate meter keeps control over this.

The moment intensity is too high—lactate above 2.5-3.0 mmol/L—they slow down. Immediately. No ego, no drama.

Now threshold work becomes a capped bet. The upside remains: strong adaptation signal, fast mitochondrial growth. But the downside—the blowup, the hole, the recovery debt—is cut off before it happens.

Capped bets can be repeated.

When a single threshold session can't blow you up, you can do another one tomorrow. And the next day. The powerful adaptation signal keeps coming. The damage never accumulates.

Both curves compound simultaneously.

Safe side: slow, steady, every day. Risky side: fast, aggressive, but controlled.

Neither cancels the other. Both build. Week after week. Year after year.

That's the asymmetry.

Traditional athletes take uncapped risks. One brutal session, three days of recovery. They're constantly paying debt.

The Norwegians cap the risk and let the upside run. Same threshold stimulus, no blowup. Then they do it again tomorrow.

The Feedback Loop

There's a third element that makes this work: speed of learning.

The lactate meter isn't about being "accurate." It's about being wrong faster.

Every session is a hypothesis: "We think Kristian can hold this pace at threshold."

The lactate reading is the test. If lactate stays at 2.5-3.0 mmol/L, hypothesis confirmed—continue. If lactate drifts higher, hypothesis refuted—slow down immediately.

This happens in real-time. Not after the session. Not the next day. Right there, between intervals.

Fast feedback loops mean fast learning.

Bu's team didn't design the perfect training program upfront. They built a system that corrects itself constantly. Daily adjustments, not quarterly reviews.

As Bu explained: "The sheer amount of data that we could now collect on them would now bring a far higher accuracy and repeatability of their condition and day-to-day changes than we ever had before."

Most training programs are built on assumptions that get tested once a quarter—maybe at a race, maybe at a lab test. By then, you've spent months training at the wrong intensity.

The Norwegians test their assumptions every single session. Wrong today, corrected today. The learning compounds as fast as the fitness.

Part 4: 10,000 Hypotheses

The Weirdness

Yes. I just wrote 3,000 words about Norwegian triathlon for an analytics and reporting newsletter.

Mitochondria. Lactate. Fat oxidation. Threshold zones.

Here's why.

I've written before that tracking doesn't start with measurement—it starts with thinking. Every metric is a hypothesis. Every dashboard shows what used to matter, not what will matter. You build models to burn models.

The Norwegians are the clearest example I've ever seen of this principle in action.

They didn't start with lactate meters. They started with a question: how do we learn faster than anyone else without destroying ourselves?

The lactate meter came later—as a tool to validate thinking, not replace it.

The Number

I pulled data from Vidtao—our database tracking YouTube ad spend across thousands of brands.

The top 10 direct response spenders have each tested between 5,000 to 10,000 ads.

Five to ten thousand hypotheses about what resonates with their audience.

The brands spending the most are testing the most. The correlation is almost perfect.

This isn't because they have more money, although some do. It's because they built organizations that can afford to be wrong 9,900 times while finding the 100 that work.

The Connection

Here's how Norwegian method connect to our world:

Blummenfelt's team tests hypotheses every single session. "We think he can hold this pace at threshold." Lactate reading comes back. Hypothesis confirmed or refuted. Learning happens immediately.

These brands test hypotheses every single day. "We think this hook will resonate." Data comes back. Hypothesis confirmed or refuted. Learning happens immediately.

Both built structures where:

Each test has capped downside (controlled intensity / cheap production)

Each test generates learning that compounds

Fast feedback loops mean fast correction

Volume of tests beats quality of guesses

The lactate meter doesn't tell Blummenfelt what WILL work. It tells him—fast—what ISN'T working. That's the whole game.

Your tracking should work the same way. Not predicting winners. Falsifying losers. Fast.

The Bratrax Principle

This is what we're building toward.

Every tracking plan is a collection of conjectures, not truths. Every metric is right until the moment it's wrong.

The goal isn't to find the perfect dashboard that tells you what to do. The goal is to build infrastructure that lets you test more hypotheses than your competitors, learn faster, and not go bankrupt doing it.

The Norwegians didn't find a secret training method. They built a system for learning faster while staying alive.

The top DR brands didn't find winning ads. They built a system for testing more hypotheses while staying afloat.

The question isn't "what should I measure?"

The question is: Are you building a business where you can learn faster than anyone else while not going bankrupt?

That's it. That's the whole question.

Your answer will look different than theirs. It has to. Your context is yours.

But the question is the same.